The number one question I get when people finish Dead Egyptians is, ‘How much of this is real and how much did you make up?’ The book has a very specific mythology and set of magical rules by which the characters must abide. Some of it does come directly from Ancient Egyptian religious thought. At other times, I filled in the blanks or even added to the mythology. Spoiler alert: I discuss many ‘reveals’ in this article.

Let’s start with what comes directly from Ancient Egypt. The concept of a Sahu is an ancient one – it translates to immortal being, or incorruptible being. If you were such a nauseatingly good person in life that you were incorruptible, you would become a Sahu – these are beings that have broken the cycle of reincarnation and do not need to start over. If you were a pretty decent person, you might end up in Amenti, which equates to purgatory. That is a sort of double of Egypt, a place to pass the years until you can take stock of whatever your sins were. If you were, on the other hand, a cruel person, one of two fates awaited you. Either Ammit (a flesh-eating monster) would get you. Or, you would fall into the waters of forgetfulness, where you would lose all memories of this life and reincarnate again. Life is hell, basically. And if you want out, you better behave.

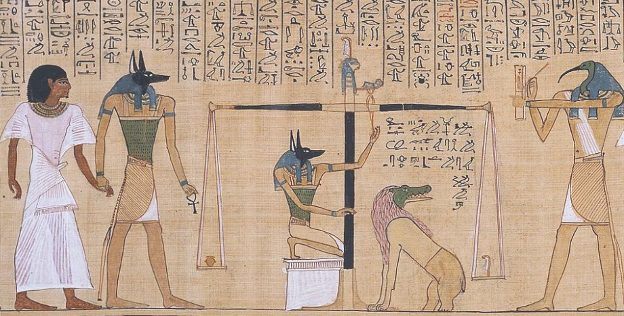

The scene in which one of the main characters dies and ends up in the Hall of Judgment is pretty true to how the Ancient Egyptians described it. There were 42 commandments, and the deceased would have to make 42 ‘negative confessions’ i.e. ‘I did not steal,’ ‘I did not lie.’ If you got past all that, your heart would be weighed against the feather of Ma’at (the feather of truth). I probably don’t need to tell you what happens to liars in the Hall of Judgment, but – you guessed it – devoured by Ammit, a flesh-eating monster who is part hippo, part crocodile, part lion, and all bloodlust.

Depiction of the ‘Weighing of the Heart’ ceremony, from the papyrus of Hunefer

The concept of the Sahu being worshipped as gods was my own supposition. You’re talking about a society that worshipped hundreds of different gods and goddesses. Surely a helper spirit, a Sahu, a being of light, could be mistaken for a god if they were to come back to earth to try to help out the living.

Statue of Imhotep from the Imhotep Museum at Saqqara

The concept of seven universal truths, which would be presented during an initiation ritual, comes from the work of Joan Grant and Elizabeth Haich. Both women were writing in the 20th century, and both women write about the initiation ritual, as well as universal truths that need to be mastered in order to pass this ritual. So that is exactly where I leave academia and discuss more arcane matters. (These women were reincarnationalists who wrote about their past lives). They are incredible books whether or not you read them as fact, and I really hope to see their work come in vogue again. Some books find the reader, and Winged Pharaoh (by Joan Grant) and Initiation (by Elizabeth Haich) were the books that, in my case, demanded to be read. Dead Egyptians could not exist without them, in fact.

In the mythology specific to my book, I defined the seven universal truths as the following:

- Transcend fear

- Transcend guilt

- Conquer discipline

- Accomplish the impossible

- Choose Peace over Violence

- Love that which you hate

- Sacrifice the thing you love most in the world

These specific masteries are fiction, however they are inspired by teachings described by Joan Grant and Elizabeth Haich.

The dead Egyptians in the novel are real historical people – Imhotep and Djoser, of course, the builders of the Step Pyramid. Rahotep and Nofret have a very famous dual sculpture. Nefermaat and Atet had a very notable tomb. Khafra, of course, is a real guy. So is Ankhaf, so is Hetep-heres. I believe the only dead Egyptian who came purely from my imagination was Sennuwy, the cobra priestess.

Rahotep and Nofret, Egyptian Museum, 2017

In the chapters where we flash back to the lives of these dead Egyptians, they are largely fiction. I studied the historical characters, and was very conscious not to write anything that went against established facts, but absolutely ran wild and used these people as blank canvases to tell a good story.

So think of Dead Egyptians as a pillared hall – the pillars are the facts – unmoveable, unchangeable. I brought in furniture and dressed it up, without moving the pillars. And if it gets people into Egyptology, so much the better. There is treasure in Egypt, and it’s not the treasure.